Today is my final day as National President of Sisters in Crime.

Don’t worry—this post isn’t going to be just a list of what I achieved. All the juiciest tidbits are behind-the-scenes stories which I can’t share anyway. *evil-girl-smirk.GIF*

What I will say is the national board accomplished A LOT while I was president. We all had our unique circumstances during this second year of pandemic life, writing and working and holding families together. My board delivered on just about every item we set ourselves at the start of my term. It was a long list, too, meticulously created over the course of my first month as president, when I held one-on-one meetings with each board member. I may have nudged here and there—only a little!—but we created that list together and we worked hard to exceed our own ambitious expectations. I am so damned proud.

Instead of that lovely, long list of checked-off items, this post will be some reflections on my past year as president, on boards in general, and on being a woman of colour in certain spaces.

(TL;DR: I loved my work as president. There’s still work to do, so pull your weight. I’ll continue to pull mine. Let’s go.)

I’ve been publishing since 2013 and joined Sisters in Crime in 2015. I’ve read our official history. I’ve heard anecdotal stories about our founding in 1986, and the vitriol directed at SinC’s founders for even pointing out the inequities in publishing between men and women mystery authors. How dare these women agitate for equal representation on bookshelves and in reviews? How dare they believe themselves worthy of attention on their own terms?

I’ve heard the snide put-down that Sisters in Crime is just a group for old women writing cozies. I don’t agree that’s a terrible group in and of itself, but, you know, patriarchy gonna patriarchy. Of course, misogynists would use women and a successful genre dominated by women to denigrate. Of course, these snide remarks would employ ageism, too, since the patriarchy judges women’s value based on sexual availability to heterosexual men.

Clearly, Sisters in Crime is still needed. Because inequities along gender lines still exist. Plus, as an organization founded on advocacy for one specific group of people who were being treated unfairly, it makes sense that SinC continues to fight for all marginalized people who have an interest or love for crime and justice writing.

Any organization that strives to thrive has to keep learning and growing.

When I joined the national board in October 2019, I was one of three non-white members. As far as I know, there were no members who identified as LGBTQIA+ or as Disabled or as Neurodiverse. (No, we don’t require anyone to self-disclose. That would be intrusive and wrong.) Based solely on conversational clues and my observational skills, I think most of the board were Gen X, with an equal number of Millennials to Boomers.

I dunno how many non-profit boards you’ve sat on, but that board makeup seemed pretty refreshing to me. Before SinC national, in my own experience of 3 very different boards/steering committees over the course of 8 years, I was always the only non-white board member, and often the youngest.

It’s a strangely privileged space, non-profit boards. You need committed volunteers with time and skills to get things done, whether your board focuses on governance or on administration. Who are the ones who can afford to work that many hours for free? Who’s had the time and energy to learn those needed board skills? It’s not usually people who look like me.

The first time someone recruited me for a board, it felt like the outgoing president’s sole criteria was “Warm body? Check!” I led a board of 10 white women, whose credentials I had no chance to review. (What can I say? They needed a new president pronto and I wanted to help.) Those women offered little support—the utter lack of onboarding should’ve been my first clue!—and even less in the way of warmth. I experienced consistent othering and exclusion. Some were so hostile, I discovered years later that they’d campaigned against so much as a thank-you card for my efforts.

All to say, the SinC national board seemed like a really interesting and promising place to do some important work.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m not holding SinC up as the end-all-be-all of membership organizations. We are pretty fucking great and we’re far from perfect. Our membership is still majority white (and majority Boomers + older Gen X), majority privileged. Tone policing, racist comments, racist assumptions, whitesplainin’—I’ve had it all.

I mean, can you truly say you’ve been a WOC in a leadership role unless well-meaning white ladies whitesplain racism and allyship to you, and then demand in all their privileged condescension that you speak out publicly against it?

The Caucasity, as the saying goes.

And yep, I understand that colourism is at play. For many, my skin colour is ranked higher on the hierarchy of acceptability. East Asians are less threatening to white supremacy, according to the rules of engagement, because of a perceived “proximity” to whiteness. Additionally, the well-worn stereotype for all Asian women is that we’re demure and subservient.

I’m by nature a collaborative person. I have noticed, however, that some people *pauses to stare in WOC* take that to mean I work by consensus. Totally not the same thing. But if they filter my actions and words through that stereotyping filter, they tend to act as though I must value their input. They assume I know less and have less experience than they do. They assume any experience I may or may not own is lesser. Thus we have white women telling me how I need to be anti-racist, to set a good example. Uh-huh.

It’s gross, it’s annoying, and it’s reality.

I’m certainly not the first SinC national board member to have brought up the urgency of anti-racist and inclusivity work. From what I know, that conversation began at least a few years before I joined the board. I know it will continue past my term, as well. Like I said, though, SinC isn’t perfect. Results don’t always reflect meaningful intentions. That’s a hard reality, too.

So I took what was supposed to be my “Legacy Project” as Immediate Past President (IPP), and I made it happen sooner, while I was president. With enthusiastic backing from the rest of the board, I created the Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (J.E.D.I.) Committee. I mindfully recruited passionate SinC members who each have lived experience with different marginalizations. I’ve chaired the committee through its first 12 months of lively discussions, thoughtful deliberations, and tangible results. I’ll continue to co-chair during my IPP term.

It’s a helluva lot of work, often tiring and seemingly endless. And it’s totally worth it.

Because we need more people from marginalized communities filling board seats. That means we need to attract a broader base of membership than what we currently have. It also means we need to make sure they feel welcomed and supported to thrive as part of our community.

I’m not talking only BIPOC members. I’m talking all marginalizations and all intersections thereof. The broader representation we have in membership, the more attention we pay to their requests and perspectives, the better an organization will understand its members’ true challenges and needs, the better it can support its communities.

I know there’s a risk of loading all the labour onto the plates of marginalized people. That’s not a new phenomenon. It’s become a wearying pattern, in fact:

- orgs ask marginalized people to take on the work of justice and equity for the betterment of the org and its members;

- orgs let them catch all the flak from privileged assholes and/or orgs weaponize their own ignorance/incompetence in such matters;

- orgs write proudly, sometimes ostentatiously, in their annual reports and PR pages that they do J.E.D.I. work;

- marginalized people burn out and leave, disillusioned and disheartened, and often, understandably, bitter.

What I think is usually missing in this awful, predictable scenario is institutional power and support.

If you’re asking marginalized people to take on the accountability of justice and equity work, then they must have the power to make change. And they must have the meaningful, vocal, and public support of the board.

I had that in my role as SinC president and J.E.D.I. Committee chair. And yes, it helped enormously that I’m also collaborative by nature. “My” board worked collaboratively as well, so we created important paths forward as a group. We may not have agreed 100% every time, but we worked together.

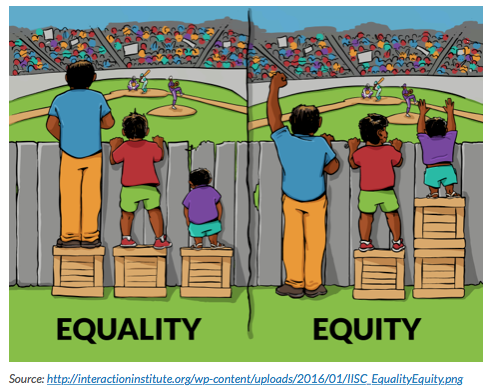

Traditional boards filled with people who are accustomed to being centred and prioritized need to educate themselves on marginalization and systemic inequities. They need to get themselves trained on how to disrupt those systems and how to use their power for the betterment of our communities. They need to understand that equality and equity aren’t interchangeable terms.

Remember when I mentioned whitesplaining above? Those are the kinds of well-meaning, privileged people we need power and support to straighten out, too. Not only the overt bigots. The latter naturally get called out more often; I mean, they practically ask for it. But the former is the group who consistently undermine J.E.D.I. work because they refuse to fully accept their complicity, and they deflect from dismantling their own, often unexamined, defences against meaningful progress.

For every overt bigot we can pinpoint, we have to weed out at least 10 self-proclaimed “allies.” We need them to do the work. Instead, they bristle at reminders of their complicity and demand kudos for clearing the low bar they’ve set themselves.

I wasn’t kidding or exaggerating when I said it’s exhausting and overwhelming work.

But I wasn’t kidding either when I said it’s worth it. It has to be. For all our futures.